By Jon Danzig, award-winning medical journalist [email Jon Danzig]

Introduction

It’s seven years since the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists last produced guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acromegaly. Their 2004 guidelines were just 13 pages long. Their latest, the 2011 guidelines, have grown – to 44 pages.

In 2004, the Association reported acromegaly as an “uncommonly diagnosed” disorder with an annual estimated incidence of 3-4 cases per 1 million people. In the 2011 guidelines, it’s added that newer studies suggest a much higher incidence (although I believe the authors meant prevalence, not incidence). A Belgian study proposing 130 cases per million; a German study concluding 1,034 cases per million. This, reports the Association, suggests that acromegaly “may often be under-diagnosed”.

In 2004, the guidelines made no mention of the psychological damage caused by acromegaly. In contrast, the new 2011 guidelines discuss possible irreversible “psychological alterations” associated with the disease, including depression, mood swings and personality changes. Similarly, the 2004 guidelines made no reference to acromegaly patients ‘quality of life’. By comparison, the new guidelines acknowledge that patients with active acromegaly, and even those in remission, can have significant quality-of-life issues that it recommends should be addressed.

The 2004 guidelines agreed that the gold standard check for acromegaly was an oral glucose tolerance test, with a normal result being a growth hormone level of less than 1 ng/mL. The Association now suggests that be changed – to less than 0.4 ng/mL.

Although the 2011 guide doesn’t report any new drugs since 2004, novel ways of combining the existing drugs are featured, with efficacious and cost benefits.

And yet...

- Both the 2004 and the 2011 guidelines report no change in the delayed diagnosis for acromegaly – it’s still up to ten years.

- Both the 2004 and 2011 guidelines report no change to the proportion of patients found with large tumours – it’s still around 80%. For them, surgical cure rate, even in the best hands, is still 50% or less.

- Many patients with acromegaly still have uncontrolled disease.

- Even those in remission can suffer “quality-of-life” issues years later.

- Most people with acromegaly, of which there may be many more thousands than previously realised, remain undiagnosed.

Below I have presented my own stylised summary of the 2011 guidelines. This I’ve put together mainly for patients, their families and friends, and primary care attendants, all of whom can play a vital role in the earlier detection of this potentially life-threatening condition.

Defining

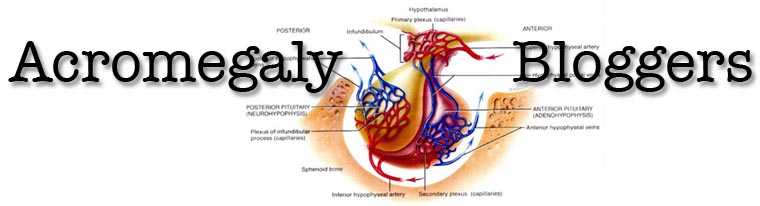

The definition of acromegaly is clear enough: it’s the excess secretion of growth hormone, causing “multi-system associated morbidities” and “increased mortality.” In almost all cases, the cause is a non-cancerous tumour of the pituitary, a pea-sized gland that’s situated at the front base of the brain and responsible for producing hormones that drive many vital functions of the body.

There’s no doubt that acromegaly is a serious illness, with a long list of debilitating and often disfiguring symptoms. (Hardly “relatively symptom-free” – the claim made by one ‘expert’ doctor that caused me considerable problems when I objected. See The Guardian newspaper report: ‘Charity accused of mistreating its members.’)

The Association’s new guide reports that acromegaly can lead to “a myriad of soft tissue and bone overgrowth” problems. Most patients (86%) will present with enlargement of their extremities (hands, feet, nose), excessive perspiration (up to 80%), thyroid nodules (73%), joint pains (75%), facial changes (74%), sleep apnoea (70%), carpal tunnel syndrome (up to 64%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (56%), and headaches (55%).

About half of patients will have a pituitary tumour that also secretes excess prolactin, a hormone primarily responsible for stimulating milk production after childbirth. This hormone, in surplus, contributes to menstrual problems in women and testosterone deficiency and sexual dysfunction in men.

Almost half of patients will present with high blood pressure, impaired glucose tolerance and heart disease. Many acromegaly patients commonly report fatigue and weakness. And new for the 2011 guidelines, the Association reports that acromegaly appears to be associated with psychological changes and alterations in personality. Patients often have depression, apathy and considerable mood changes. One study suggested that acromegaly could cause cognitive impairment, but the Association advises that further investigations need to be undertaken.

Other factors include an increased risk of cancer, although a possible connection with colon cancer remains unclear. The tumour itself can also cause visual defects. My summary isn’t exhaustive. The list of recognised symptoms associated with acromegaly has grown since the 2004 guidelines. I suspect even more will be discovered in the next seven years.

The biggest risk of all, however, remains the same: untreated acromegaly is associated with a 2 to 2.5 times increased mortality compared to healthy people. Fortunately, this risk is abrogated – or cancelled – once acromegaly is properly controlled. What is the correct definition of ‘properly controlled’ is still being continuously debated and refined.

Finding

Finding and diagnosing acromegaly patients as early as possible is still the best way to achieve an outright cure and avoid the long-term disabilities associated with the disease’s progression. Yet the 2011 report states that diagnosis is typically delayed by 7 to 10 years in most patients. By then, the pituitary tumour is usually large and more difficult to completely remove with surgery.

Even in the best hands, surgical cure rates of patients with a large pituitary tumour are only between 40% and 50% (and surgery is usually considerably less successful if the tumour is very large and/or the growth hormone levels are very high).

There’s also a financial incentive to ‘find and fix’ acromegaly patients as soon as possible. Acromegaly is a disease “with a substantial financial economic burden”. In Canada, ongoing treatment for patients who had large tumours cost on average CAN $11,425 per year (about £7,000 per year; 1998 figures, no doubt higher now).

Early diagnosis of acromegaly is rarely achieved, however. That’s because, states the 2011 report, the onset of acromegaly is insidious and often non-specific, with symptoms such as lethargy, headache and increased sweating – signs often mistaken for ageing.

Surprisingly, only a fraction of patients are discovered because of the classic signs of acromegaly, that slowly develop over years (enlarged feet, hands, lips, nose and jaw; often protruding forehead and rough, pronounced facial features). Most often patients themselves are not even aware of the harmful changes happening to them, because they are so gradual.

There’s a need, reports the 2011 guidelines, for primary care physicians and other medical groups to be better educated to watch out for the signs and symptoms of acromegaly so that earlier diagnosis can be achieved.

The dentist, for example, could be suspicious of a patient whose lower jaw is protruding further than the upper jaw – a typical symptom of acromegaly patients. The optician should be alerted by a visual field defect that might be caused by a pituitary tumour. Rheumatologists often test for disorders that might also lead to a diagnosis of acromegaly.

The new guidelines propose that doctors should consider acromegaly when two or more of the following 12 symptoms are present:

- New onset diabetes

- Wide spread joint pains

- New or difficult to control high blood pressure

- Heart disease

- Fatigue

- Headaches

- Carpal tunnel syndrome (pain in hand and fingers)

- Sleep apnoea (snoring with breathing difficulties)

- Excessive sweating

- Loss of vision

- Colon polyps

- Increasing difficulties in closing the jaw

IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) is produced by the liver in response to growth hormone secreted by the pituitary gland. IGF-1 then circulates in the body and stimulates cell growth. In acromegaly, excessive growth hormone generated by the pituitary tumour leads to the liver over-producing IGF-1.

A random one-off measurement of growth hormone itself is not helpful as it’s too variable. Measuring growth hormone levels to diagnose acromegaly requires a more specialist procedure, called an Oral Glucose Tolerance Test, and is still considered the ‘gold standard test’ for acromegaly.

After drinking the glucose following over-night fasting, blood is taken every half-an-hour for two hours. In patients without acromegaly, serum growth hormone levels will fall to 1 ng/mL or less (although the Association is now considering a new cut-off point of 0.4 ng/mL). In patients with acromegaly, the glucose fails to suppress growth hormone levels and they remain above 1 ng/mL.

However, the new guidelines also state that this ‘gold standard test’ can be skipped altogether if IGF-1 is elevated and there are signs and symptoms of acromegaly. That certainly makes diagnosis simpler, quicker and cheaper.

Following confirmation of acromegaly, an MRI-scan should be ordered to check the size and exact location of the tumour attached to the pituitary gland.

Patients diagnosed with acromegaly need to be regularly re-tested for the rest of their lives. The pituitary tumour has been known to recur, sometimes many years later.

‘Fixing’

Most patients with acromegaly are never fully ‘fixed’ or entirely free of the disease and its long term damage. Some may disagree, but I believe it can be postulated. After all, it’s rare for chronic internal medical diseases to be 100% ‘fixed’; more usually it’s hoped that they can be improved or put into remission or controlled.

As Professor Laurence Katznelson, Chair of the committee that drew up the new guidelines, wrote to me, “Many patients with acromegaly are left with residual difficulties."

Subsequently, some acromegaly patients have also written to me saying it’s inappropriate for doctors to use the term ‘biochemical cure’ - meaning their blood test results no longer show signs of acromegaly – when they continue to suffer debilitating symptoms.

Out of 100 patients discovered with acromegaly, about 20 will have a small pituitary tumour and about 80 a large one. Depending on which surgeon operates, surgery alone will result in a ‘biochemical cure’ in only about half, more or less, of the 100 patients. Medication or radiation will achieve ‘biochemical cure’ in many, but not all, of the rest.

Although ‘biochemical cure’ is now much more achievable than previously, and can result in considerable improvements for patients, it’s agreed that it doesn’t necessarily equate to satisfactory elimination of the disease and its consequences in many patients.

This is discussed in the new guidelines, which report that many patients who have been in ‘biochemical remission’ for years continue to suffer quality-of-life issues, especially relating to musculoskeletal complications resulting in significant joint pains. Adverse changes to appearance caused by the disease can also cause profound difficulties. Unlike soft tissue changes in acromegaly, bone enlargement caused by the disease is permanent.

Significant psychological issues can also persist despite the biochemistry apparently being in normal range. The new guidelines raise the possibility that acromegaly can cause irreversible changes to mood and behaviour. The authors recommend that all acromegaly patients, whether with active disease or in remission, have attention to quality-of-life issues.

Also of interest, acromegaly appears to affect both sexes and all races in equal proportions.

There’s no known way to avoid getting acromegaly, since so far we are not even sure what causes it in the first place. The best chance for patients is to be discovered in the very early stages of the disease, when the tumour is small and there’s the highest chance of a real cure through surgery alone. For the rest, the majority, the doctor’s toolbox is limited: to surgery, medication or radiation.

The new guidelines report five goals in the treatment of acromegaly:

- To bring the chemical measures of acromegaly to normal

- To control the size of the tumour

- To reduce the signs and symptoms of the disease

- To prevent or improve medical conditions related to the disease

- To prevent premature mortality

Surgery – it remains the most effective option to achieve rapid and complete cure for all patients who can have surgery. Even if cure doesn’t occur, the reduction in tumour mass can result in considerable recovery and also improve the response of subsequent medication. These days most pituitary surgery is endoscopic transsphenoidal through the nose, which is minimally invasive. The most experienced surgeons – those performing at least 50 transsphenoidal procedures a year – have the best outcomes with low mortality and morbidity.

Medication – for those who cannot have surgery, and for those for whom surgery did not result in a ‘cure’. There is also some evidence, according to the new guidelines, that medication taken prior to surgery might result in a better post-operative outcome.

There are three classes of medical therapy: dopamine agonist, somatostatin analogues and a growth hormone receptor antagonist:

*Dopamine agonist – (tablets) usually cabergoline. Sometimes used as a first-line medical therapy because it’s taken orally and inexpensive. However, it’s only effective in a minority of patients, and usually only considered for patients with ‘mild’ acromegaly.

*Somatostatin analogues – (injections) usually octreotide LAR or lanreotide autogel. The new guidelines report that with this medical therapy, about 55% of patients achieve normal growth hormone and IGF-1 levels. The medication can also result in modest or significant reduction in tumour size in some patients. There have been mixed studies of whether treating with somatostatin analogues prior to surgery improves the results, and the guidelines authors state that further study is needed on this.

*Growth hormone receptor antagonist – (injection) known as pegvisomant, this is the most efficacious but unfortunately the most expensive of the drugs available. It works in a completely different way to the other medications. In patients treated with pegvisomant for a year, the new guidelines report that IGF-1 levels were normalised in 97% of patients, confirming it to be the most effective drug currently available. Patients also reported improvements in their signs and symptoms of acromegaly. To be cost effective, however, the guidelines report that the price of pegvisomant needs to be reduced by one third.

*Combination therapy: the new guidelines describe some success with combining the medications when one alone didn’t work sufficiently. For those who only partially responded to somatostatin analogue treatment, the addition of cabergoline helped 42% of them to achieve normal IGF-1 levels. The guidelines also reported that the combination of somatostatin analogues with pegvisomant often appeared to be more effective in normalising IGF-1 levels than either drug used on its own. In one study (featured in the guidelines) the addition of weekly pegvisomant to somatostatin analogue treatment resulted in IGF-1 levels becoming normal in 95% of patients. Another study (not in the new guidelines) demonstrated that this combination resulted in significant improvements to patients’ quality-of-life. Since this combined therapy usually involves lower doses of both drugs, it’s been argued that this can result in cost savings over the use of one drug alone.

Radiotherapy – usually used as a last resort, when surgery and medication haven’t worked. However, the guidelines report that with the availability of effective medication, the role of radiotherapy has subsequently diminished. It is, though, still used to reduce the need for (expensive) lifelong medication and with a goal of ‘disease cure’.

One downside is that it takes a long time for the radiation to work – from several years to over a decade. The guidelines state that techniques for radiotherapy have improved in recent years, with better targeting to the tumour and subsequently less radiation exposure to surrounding tissue.

The results of the more old fashioned ‘conventional radiotherapy’ have recently been reassessed to take account of the stricter criteria of ‘biochemical cure’ for acromegaly. Whereas previously it was thought that conventional radiotherapy resulted in a remission rate of over 80%, that’s now been revised considerably downwards to just 10 to 60%. Furthermore, conventional radiotherapy can take about ten years to be effective – even longer in patients with initially higher IGF-1 and growth hormone levels.

The more modern radiotherapy is called stereotactic radiosurgery, of which there are several versions, but the new guidelines concentrate on reporting ‘gamma knife’ radiosurgery, because it’s the one most referred to in the medical literature for acromegaly. With this newer, more precise form of radiation, remission can sometimes be achieved in two years, rather than ten for the conventional form of radiotherapy. Earlier studies reported remission rates of 90% for gamma knife radiosurgery, but again, with the stricter definitions of cure, this has now been revised to just 17 to 50% remission rates during two to five years of follow-up. The guidelines state that further studies are needed over a longer time-frame.

There are, however, significant drawbacks to radiotherapy, report the 2011 guidelines. One is the development of hypopituitarism –or failure of the pituitary gland – in more than half of patients after five to ten years. Hypopituitarism has been linked to increased mortality. The authors also point out that similar prevalence of hypopituitarism has been found with the more modern stereotactic radiosurgery, although most studies so far have only reported on less than six-years average follow up for gamma knife radiosurgery.

In a recent talk to doctors (not mentioned in the new guidelines) by Professor John Wass, one of the world’s foremost experts in acromegaly, he said, “In the olden days people gave radiotherapy, really without thinking, to patients with pituitary tumours.” He added that the side effects of conventional radiotherapy include hypopituitarism; some patients develop tumours in the field of the radiotherapy; mental agility was also thought to be interfered with; and radiotherapy may also cause acromegaly patients, ironically, to become growth hormone deficient.

Regarding the newer form of radiotherapy, Professor Wass commented, “I don’t think that the data that have been provided for gamma knife radiotherapy are particularly good.”

The new guide also raises similar concerns about radiotherapy, and points out that acromegaly patients who received conventional radiotherapy were at significant greater risks of “all-cause mortality” than those who did not receive the treatment. The 2011 guidelines advise that long-term data of such risks for patients undergoing the more modern gamma knife radiosurgery are not yet available, since most of the data relates to the older forms of radiation delivery. The newer systems may potentially yield better results, but we will not know until longer-term data become available.

My conclusions

The goal of the new guidelines is to, “update clinicians regarding all aspects in the current management of acromegaly...” Patients also need updating, and I’ve tried my best to summarise the latest recommendations primarily for the benefit of patients, although hopefully physicians will find this summary helpful too.

Given a choice, this is actually the best time ever to have acromegaly. You only have to go back to the middle of the last century – within the lifetimes of many of us – when the prospects for acromegaly patients were much grimmer, with fewer therapeutic options and more premature deaths. We’ve come a long way, but not far enough. Most acromegaly patients remain undiagnosed, and most of those who have been diagnosed had to wait an awful long time, and still suffer long term symptoms.

Doctors and drug companies supply, but often only after patients demand. With doctors, patients and drug companies working together, I’m hopeful that the next guidelines issued by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists will be able to report faster diagnosis times, a more realistic definition of ‘cure’ and better therapies to achieve either a real cure, or at least substantially improved outcomes.

Jon Danzig is a medical journalist and writer/director of short films. He won a Lilly Medical Journalism Research Award for his medical articles, primarily about amniocentesis, episiotomy and women being sterilised ‘against their will’. He was an investigative journalist on the prestigious BBC Checkpoint programme; a freelance correspondent in the USA, and ran his own successful media business, Look-Hear.com. Jon’s growing list of short films can be seen on his new YouTube channel at JonDanzig.com Jon was recently interviewed on BBC Radio about his life and career: Jon Danzig BBC Radio Interview. Click here to view Jon’s Linkedin profile.

Jon’s favourite quote: “Knowledge is power” – Sir Francis Bacon

Declared interest:

The author has acromegaly, and has written extensively about how the illness has affected his life and career. ‘My DIY Diagnosis’ – The Independent Newspaper;‘Acromegaly – A Patient’s Journey’ – British Medical Journal; ‘Challenging Doctors’ – Acromegaly.org; ‘Challenging Sleep’ – Pituitary Network Association. ‘No rest for the wilted’ – The Guardian newspaper

(via NewsMedical)

No comments:

Post a Comment